Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, promises naval forces unprecedented autonomy at sea, such as the ability to print replacement parts in hours rather than wait weeks for resupply. However, a 2016 experiment that brought down a drone with corrupted design files exposed a critical vulnerability which poses risks to widespread operational adoption. Until navies can guarantee both digital security and physical reliability, 3D printing will likely remain confined to non-critical systems.

What if all it took to bring down a military drone was a corrupted 3D printer file? No explosives, no jamming, no physical interference—just a few lines of malicious code buried in a blueprint. That’s exactly what a team of researchers demonstrated in 2016 when they hacked into and modified the digital design of a drone’s 3D-printed propeller. The part looked flawless. But mid-flight, under load, it shattered and the drone dropped. The mission was over within minutes, not because of enemy fire, but because of a flaw no one could see, in a part no one ever physically touched.

The 2016 Dr0wned experiment was not a fluke. It was a warning. As navies turn to AM for spare parts, mission-specific tools, and unmanned systems, the appeal is obvious: speed, autonomy, resilience. But its use remains limited to non-critical parts. Why? Trust. Trust that design files haven’t been compromised. Trust that printed parts will hold under pressure, in unforgiving environments.

Beyond logistics: The strategic return on investment

In 2022, the US Navy (USN) launched its Additive Manufacturing Center of Excellence in Danville, Virginia. Two years later, sailors aboard USS Somerset 3D-printed a replacement part for the ship’s desalination system mid-mission during RIMPAC 2024. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) took things further with a full deployable 3D printing lab – the DAMR system – fielded during Talisman Sabre 2025. And every Royal Netherlands Navy (RNLN) ship now sails with onboard 3D printers as standard issue.

These examples reflect a broader shift. AM is becoming a practical tool for navies seeking greater independence, flexibility and responsiveness at sea. Where a failed bracket or worn pipe once meant weeks of delay, it can now be replaced in a matter of hours. “One of the main benefits is that it allows deployed ships to become more self-sufficient and reliant,” said Max Nijpels, AM engineer at the RNLN Expertise Centre for Additive Manufacturing (ECAM). For navies that routinely operate far from home – including the RNLN, USN, RAN, Royal Navy (RN) and Marine Nationale (MN) – that self-sufficiency directly enhances operational availability.

Beyond logistical speed, AM offers a path through obsolescence. Where Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) ceased production or disappeared altogether, additive methods allow crews to reproduce components that would otherwise be unavailable. As Nijpels noted, the long-term aim is to embed AM into the naval supply chain – not as a last resort, but as a core capability that increases fleet readiness.

The economic case is no less compelling. A 2019 study by the US Naval Postgraduate School, titled ‘Additive Manufacturing Laboratories at Sea and their Value to the Navy’s Seagoing Warfighter’, concluded that AM laboratories at sea could generate a 234% return on investment and a 334% return on knowledge. The analysis concludes: “Because AM could potentially play a major role in manufacturing time-sensitive parts on demand for sustainment and readiness for entire Battle Groups at sea, AML installation on naval vessels clearly provides a value-added capability to the Navy.”

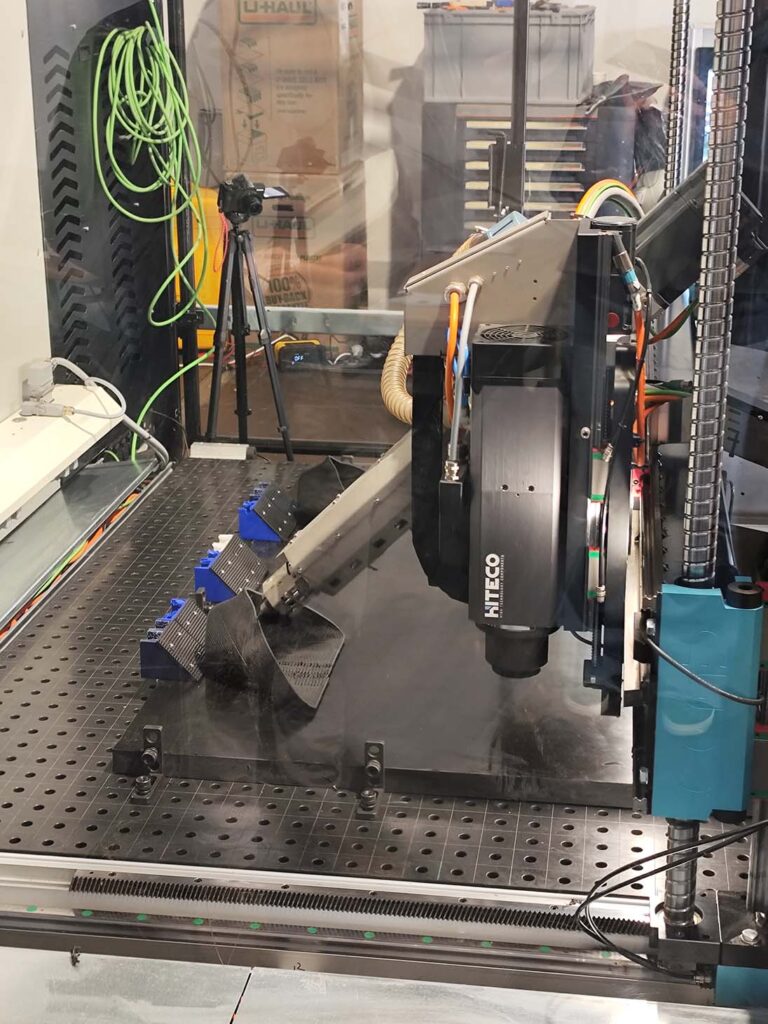

More recently, AM has also been used to experiment with rapid prototyping. At the Bold Machina 2025 exercise, held at the Nieuwe Haven naval base in Den Helder, The Netherlands, during September 2025, special forces from multiple nations collaborated on the design and deployment of an unmanned surface vehicle (USV).

The hull was printed on site by Dutch company CEAD using ruggedised thermoplastic composites, while commercial off-the-shelf components filled out the navigation, propulsion and sensor suite. “This was not just about printing parts, it was about proving that special forces can locally manufacture and deploy functional systems within hours, without relying on fragile supply chains” explained Charlene van Wingerden, Chief Business Development Officer at CEAD.

This provided flexibility and the ability to quickly iterate between designs. For instance, the officer overseeing the training told journalists: “One of the battery packs didn’t fit quite right in the first version, so we just updated the Computer-Aided Design (CAD) file and printed a new one the next morning. That kind of iteration would take weeks in a normal setting.” The goal was not simply to build a boat, but to demonstrate that functional, mission-specific platforms can be generated quickly and affordably – even by users with no robotics background. In doing so, the exercise underscored AM’s growing potential to support rapid prototyping and tactical innovation at the edge.

Yet for all the benefits it offers and the promises it holds, AM remains largely experimental in most navies. The RNLN is among the few that have already integrated it more systematically. The technology itself is no longer the barrier, with large-format printers now producing USV hulls within hours, and smaller systems routinely accelerating supply workflows. Rather, the constraint is operational: most applications remain confined to non-critical systems. As with AI, broader adoption hinges on a single factor: trust.

The invisible saboteur: When the file is the weapon

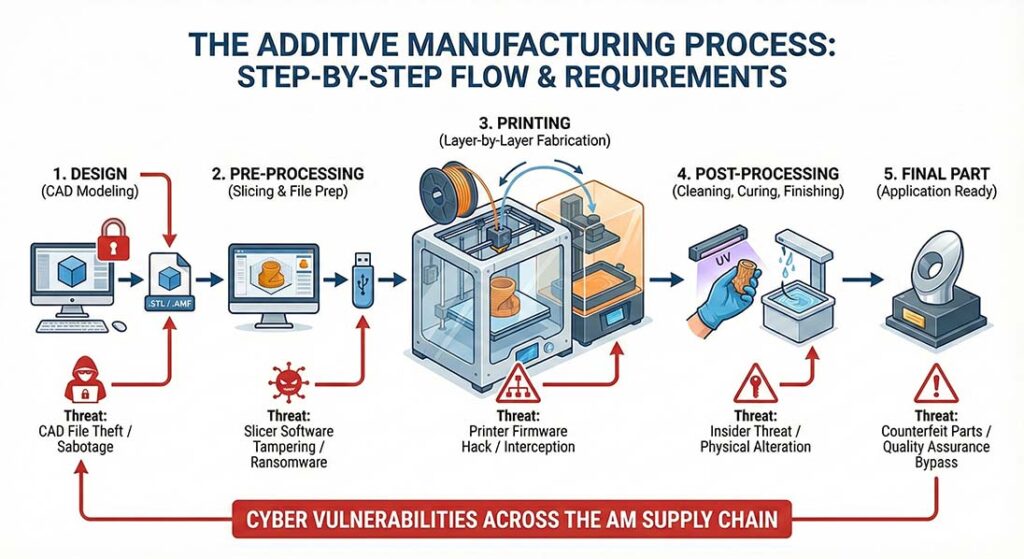

At its core, AM is a digital process. From design to print, a part exists solely in the digital space – first as a CAD file and then as a Technical Data Package (TDP). For navies, the process begins even earlier: the moment a deployed unit requests a TDP to replace a component, it steps into the digital domain – and creates a chain of potential cyber vulnerabilities.

The 2016 Dr0wned experiment illustrated this risk. Conducted by researchers from Ben-Gurion University, the University of South Alabama, and the Singapore University of Technology and Design, it demonstrated how a malicious actor could infiltrate the AM process for a USD 1,000 drone and introduce subtle flaws into one of its critical components. The attack began with a phishing email containing a malicious PDF. Once opened, it installed remote-access malware, allowing the attackers to locate the drone’s blueprint, alter the propeller design, and let the 3D printer execute the rest. Visually, the defective propeller was indistinguishable from the original. But mid-flight, under basic aerodynamic stress, it shattered, bringing the drone down.

Nearly a decade later, cybersecurity awareness has advanced, especially within armed forces. Navies now operate cybersecurity centres and task specialists with managing digital risks aboard increasingly connected vessels. Still, within the broader force, the implications of system-of-systems integration and the Internet of Things (IoT) are not always fully understood.

A 2021 audit by the US Department of Defense (DoD) Inspector General, titled “Audit of the Cybersecurity of Department of Defense Additive Manufacturing,” found that AM systems at several reviewed sites were not consistently secured or managed to prevent unauthorised modifications or protect the integrity of design data. One core issue was perception: AM systems were seen as tools to generate parts, not as networked IT systems requiring appropriate cybersecurity controls.

This is a critical gap. AM systems operate within broader naval networks. Misunderstanding this context opens multiple attack vectors. Beyond sabotaging a physical part, a network intrusion could enable intellectual property (IP) theft, allowing adversaries to reverse-engineer capabilities or identify structural weaknesses. Intercepting an unsecured TDP request could reveal mission-critical vulnerabilities. “Imagine sending a request for a weapon system’s spare part TDP, or carrying out a remote survey to certify that spare part,” Nijpels explained, “you definitely would not want your adversary to know that you are one weapon system down!”

Perhaps even more worrying is the latest research from a team of researchers from the University of Louisiana and Auburn University. In a 2024 paper, “Decoding Intellectual Property: Acoustic and Magnetic Side-channel Attack on a 3D Printer”, they demonstrated that direct intrusion with an AM process may not even be necessary to carry out IP theft. To translate a 3D model into layer-by-layer instructions, AM uses G-code, a programming language that dictates the printer’s movements to create the object. Creative attackers could utilise a smartphone’s built-in sensors – including the microphone – to capture this data and reverse-engineer the parts.

While such an attack might seem implausible in naval settings where smartphones are restricted or offline, it underlines a broader truth: cyber threats evolve quickly, and attackers are often more imaginative than expected. Cybersecurity remains a constantly moving target.

Securing the digital supply chain

Yet as with all things cybersecurity, all is not doom and gloom. As with most digital systems, the key lies in identifying potential vulnerabilities and developing effective mitigation strategies.

For the RNLN, the solution – at least for now – is very clear: to serve its fleet of 3D printers, files are stored and uploaded on secure internal communication networks and 3D printers are never connected to external networks. This is essential, explained Max Nijpels, because most of the RNLN fleet lacks digital twins – there is no comprehensive digital record of spare parts. “But we are working on creating a database for AM parts that will be available on all ships and will remove the need to contact ECAM when they need spare parts,” he said.

In practice, when a ship requires a spare part, the crew submit a request to ECAM, which provides the TDP through the secure network. The part is printed onboard and fitted to the system. Building this database will take time, but the benefits are already clear. “Once a digital version of a part has been created, the entire RNLN and Marines fleet can benefit from it,” Nijpels added. Ultimately, this will streamline workflows and enhance cybersecurity.

The US DoD took a similar step in 2020 by launching JAMMEX (Joint Additive Manufacturing Model Exchange), a secure, centralised web-based repository. It allows personnel to access pre-approved 3D models validated by engineering authorities such as DLA and NAVSEA.

And to support secure interoperability across allied navies, NATO developed RAPID-e (Repository for Additively Manufactured Products in a Digital Environment), a digital library that enables the secure storage and exchange of TDPs. It ensures that a certified file retains its status when printed by a different nation. RAPID-e became operational in December 2024.

Of course, even a secure repository may present potential vulnerabilities. That is why the US National Innovation Advisory Council (NIAC) announced in 2017 that it would start exploring blockchain technology to secure 3D printing processes. It is however difficult to assess how far the NIAC efforts have gone as there appears to be no publicly available information past 2021.

The certification gap: Why ‘good enough’ isn’t enough

Closely tied to cybersecurity is the question of certification. Without it, trust in 3D-printed parts remains limited. If crews can verify that a printed part or process has been certified, they can use it with confidence. Had the Dr0wned experiment included a certification step, the flaw in the drone’s propeller would likely have been caught, and the mission completed.

For shore-based production, certification is more straightforward. Classification societies like DNV (Norway), Lloyd’s Register (UK), and ABS (US) are actively working with industry to streamline certification. Their efforts are guided by the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS), which released Recommendation 186 in 2025 – a framework for qualifying and certifying 3D-printed metal parts for marine use. This is how, when a chilled water pump cooling rotor failed aboard an Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyer, it was replaced within weeks at a fraction of the cost: just USD 131.21 for the printed blade, versus USD 316,544.16 to replace the entire motor through conventional means.

But certification of parts that have been 3D printed while on deployment is tricky. A CAD design for a part may have been certified, but replicating it in a maritime environment introduces variables: salinity, humidity, vibration, and sea state can all affect print quality. The RNLN’s ECAM tested its UltiMaker FDM printers aboard the logistics support ship HNLMS Pelikaan under different sea conditions. “At the time we found that, while sea states did not appear to affect the quality of the printing, engine vibrations did,” Nijpels explained. The solution was simple: relocate the printer to a more stable area of the ship.

But these variables raise broader questions, particularly around liability. If a printed part fails and damages a critical system, who is responsible? The OEM that provided the original design? The printer manufacturer? The ship’s crew?

Data-driven trust: Remote surveys and in-process monitoring

To some extent, certification bodies are beginning to confront the challenges of remote and in-situ validation. DNV’s In-Process Monitoring standard, DNV-ST-B203, shifts focus away from certifying individual parts and toward certifying the process itself – including the machine and its feedstock. The rationale is straightforward: if the printer is calibrated and the material verified, the output can be trusted – within defined limits. Yet those limits may be challenged under conditions aboard naval vessels, where environmental factors such as vibration, salinity, and temperature variability challenge consistency.

In the commercial sector, remote surveys are advancing rapidly. In 2018, Lloyd’s Register began collaborating with The Welding Institute (TWI) based in Cambridge, UK, to develop remote technologies and smart sensors for surface and subsurface inspections in hazardous environments. In the US, ABS has issued guidance for the safe use of remote inspection technologies.

As for industry, van Wingerden told ESD that certification always lags behind innovation, especially when new materials and new processes enter naval workflows. “What we do today is make the process as controlled and traceable as possible,” she explained. “Our machines log extensive process data, monitor key parameters in real time and maintain strict repeatability. That foundation is essential, because once certification frameworks catch up, the question will be whether the process is trustworthy.”

These tools promise agility and reach, but naval conditions add complexity. In an environment where connectivity can be spotty at best, and where the safe encryption/protection of that connectivity is paramount, can remote surveys really be the solution?

Nijpels pointed to a possible future where in-process monitoring is combined with artificial intelligence (AI). “Carefully developed algorithms could be used to detect if there is an issue, even a cyber issue, in the printing process or the integrity of the material,” he explained. Such systems could offer real-time validation and deeper confidence in parts produced at sea.

Command trust: The final component

For all its potential, AM remains a capability in search of command trust. Cybersecurity and certification are not just technical hurdles – they are operational bottlenecks. Until navies can ensure that a part is both digitally secure and physically reliable, 3D printing at sea will remain largely confined to non-critical systems and non-mission-essential repairs.

To address this, several organisations are developing tiered approaches to trust. The US’ Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) has introduced a ‘green box’ system, a framework that works on a tiered model going from low-critical parts to highly-critical parts and, as such, delineates what can be printed, by whom, and under what conditions. The RNLN applies a similar concept, calibrating risk by type of part, application, and certification level. This tiered model helps commanders make informed decisions: they don’t need to trust everything, just the right things, in the right context.

In the meantime, AM will continue to prove its value where the stakes are manageable. At the Bold Machina 2025 exercise, the goal was not to develop the state-of-the-art, but “the state of the possible,” as one trainer put it. That mindset – experimenting within safe operational boundaries – may be the key to unlocking wider adoption.

Industry actors are also working toward the same end. Certain companies developing large-format naval AM systems see the path to wider adoption as running through process reliability. “If commanders can see exactly how a part was printed and if those parameters are consistent every time, then certification becomes an exercise in validating the process rather than re-inspecting every part,” van Wingerden explained. Such data-rich workflows do not replace certification, but they can accelerate it once standards mature.

As navies move from pilot projects to scaled implementation, trust will remain the bridge between experimentation and doctrine.

Dr Alix Valenti

Author: Dr Alix Valenti is a freelance defence journalist with 10 years’ experience writing about naval technologies and procurement. From 2017 to 2019, she was Editor-in-Chief of Naval Forces. Alix holds a PhD in post-conflict reconstruction.