In 2025, the Western Balkans has become a key indicator of Europe’s changing security order, shaped by increased militarisation, new partnerships and increasing external influence. The impact of the war in Ukraine continues to felt across the region, exposing vulnerabilities and forcing defence modernisation. Simultaneously, rival external actors – from Türkiye to Russia and China – compete aggressively for access and strategic leverage over the EU and NATO. The result is a region that is still trying to stabilise while at risk of becoming increasingly destabilised, something that is inadvisable for the West to ignore.

The Western Balkans has long been viewed as a bothersome sub-region of Europe, best known for its unresolved historical legacies, ethnic tensions and problematic inter-state relations. But with the war in Ukraine showing little sign of abating, the region is now moving ever closer to the spotlight of Europe’s defence and security architecture. It does so not as a peripheral concern, but as a strategic region in the EU’s quest for resilience among its current and prospective members. The impact of Moscow’s aggression is reverberating throughout this southern periphery; hybrid threats are increasing and age-old fault-lines are re-emerging. In the current European security environment, this restless region is not only reacting to today’s geo-political realities, it is also readjusting. In 2025, defence spending has continued to rise across the board, with new joint frameworks emerging and external players repositioning themselves.

As 2025 draws to a close, what matters today is not just about arms, equipment or defence budgets, but the messages being delivered, both within the region and outside: with whom are states in the region cooperating; which external players are active, and how do the region’s vulnerabilities (ethnic tensions, economic frailties, challenged statehood) blend with newly emerged threats, including cyber, drones, and hybrid warfare? For defence industry observers and policy analysts, the Western Balkans at the end of 2025 provides both opportunity and risk.

Back on the agenda

The region’s new relevance is framed by several interconnected trends. The ripple effects of Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine have triggered increased defence budgets, new security alignments and a more assertive outreach to external actors. States in the region that had long been accustomed to low-intensity security dynamics, have been forced to mobilise and re-arm, with the invasion shaking the European continent’s defence posture to its core. Stability on Europe’s south-eastern flank today is seen by many observers as a pre-condition for the wider Euro-Atlantic security environment. For both NATO and the EU, a stable Balkans means fewer vulnerabilities, less trouble and fewer headaches in the long run.

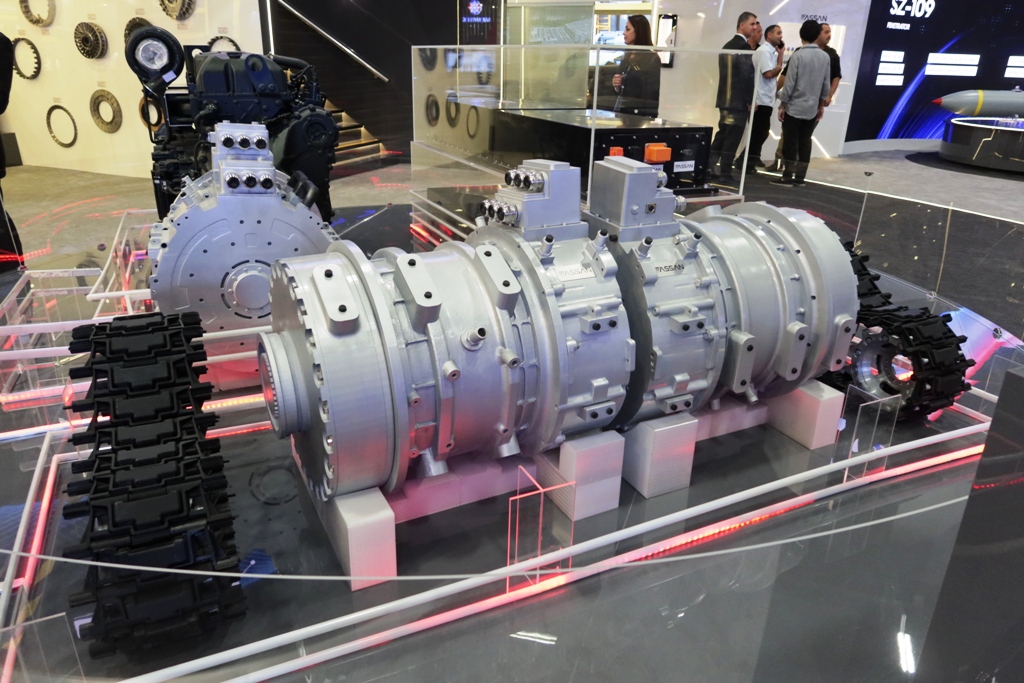

But external actors now view the region as a new sphere of influence, both for deterrence and pressuring opponents. In this regard, the EU, China, Russia, Türkiye, and Gulf-states are all actively engaged and in competition there. The Balkan conflicts of the 1990s may well have ended three decades ago, but the lingering structural fragility is exacerbated by simmering ethnic and territorial grievances. The local defence industry and procurement market has also become increasingly active. Furthermore, Balkan states are finally transitioning from Soviet-era systems to Western or mixed systems.

Defence spending and modernisation programmes

One obvious barometer of change in the area of defence is the increase in related spending, joint procurement programmes and operational reforms. Several countries are showing rising defence budgets reaching double-digits; though precise numbers vary, the pattern is consistent regionwide. The 2025 defence budget for Kosovo (1.6 million inhabitants) for example reached roughly EUR 200 million (2% of GDP). Serbia’s defence budget by comparison is approximately EUR 2.2 billion (2.5% of GDP, up from 1.8% in 2023). Some militaries are reintroducing conscription (NATO member Croatia, for example, in late 2025) and are strengthening reserve units, signalling that mobilisation preparedness is receiving renewed attention. In late 2024, Albania approved a draft law to establish a reserve force equivalent to 20–25% of active personnel — or around 2,000 reservists within the next five to six years. Procurement is not only focused on hardware, but also on modern systems, including unmanned systems, cyber defence, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), and logistics modernisation. Finally, local defence industry engagement (maintenance and local production) is increasingly being factored in, with states preferring not just to purchase, but to participate. The reasoning is simple: as Europe’s wider security challenges intensify, the Western Balkan states can no longer afford to be the bit part, low-capability players of the past. They have recognised the need to prepare for scenarios focused on deterrence, rapid reaction, and above all, resilience.

New alliances

The changing landscape of new alliances and security frameworks represents a key development in 2025. Two clear geo-strategic threads now run through the region: In March, defence ministers of Albania, Croatia and Kosovo signed a Joint Defence Cooperation Declaration, which foresees joint training and procurement coordination, technology sharing and interoperability under the umbrella of Euro-Atlantic frameworks. This alignment reflects their faith in the NATO/EU trajectory and willingness to act beyond bilateral ties. Concurrently, Serbia announced a defence agreement with neighbouring (NATO and EU member) Hungary. That pact is certainly looser and less formalised, but still important as Serbia seeks to maintain its ‘military-neutral’ posture (with no intention to join NATO). With this move, Serbia diversifies, still keeping ties with Russia open, as it does with China, while managing to continue engaging with Europe.

The significance of these sub-regional alignments is less about formal blocs and more about strategic messaging. For NATO, this moment offers an opportunity to address regional burden-sharing and increased interoperability, but it also represents a challenge – ensuring coherence and avoiding parallel structures.

Türkiye: An overlooked regional player

When viewing the region, analysts and media pay most attention to the EU, NATO, Russia and the Western Balkan states themselves, with the role of Türkiye often overlooked. But Türkiye is an influential actor in the region – economically, diplomatically, culturally and militarily – and its role has strategic importance at the end of 2025 more so than ever.

Ankara’s current involvement in the region should be seen against the backdrop of decades of defence-related engagement (centuries in fact, recalling the Ottoman Empire years). Following the end of the Bosnian war in 1995, Türkiye actively participated in the ensuing peace implementation processes, committing troops under UN and NATO auspices (UNPROFOR, IFOR, SFOR). Türkiye still has a seat on the Steering Board of the Peace Implementation Council’s (PIC) Steering Board for Bosnia and Herzegovina, representing the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC).

Türkiye’s role in the region’s security cooperation is active and expanding. According to a 2024 research article published in the Journal for Diplomacy and Strategy by Atakan Şenel, Ankara plays an “active role in regional security cooperation, contributes to the security cooperation of the region, and has the potential to support the capacity building of Western Balkan countries in specific areas such as counter-terrorism”.

Beyond military deployment, Türkiye has also established deep cultural, educational and infrastructural ties across the region through the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA); sometimes referred to as ‘infrastructure imperialism’, with over 4,000 projects implemented to date in the region, including restoration of Ottoman-era monuments and religious sites, telecommunications, and economic cooperation initiatives. More than EUR 1 billion has been invested by Turkish companies, complemented by nearly EUR 210 million in direct foreign investment. These all contribute to Ankara’s Ottoman legacy, soft-power approach and its status as a key regional stakeholder. Economic and infrastructural investment have created the foundation for Türkiye’s regional role – a blend of influence and capability.

Risks and friction

With Türkiye’s engagement driven by a mixture of strategic ambition and cultural affinity (especially in the Muslim-populated areas of BiH, Kosovo, the Sandžak region of Serbia, and Albania), some observers warn that Ankara’s role is not purely benign. They warn that it may generate dependency, foster particular ethno-religious alignments, or create parallel security architectures.

One clear example of Türkiye’s support is for Kosovo’s defence capacities, something that has triggered acute concern in Belgrade. Here, it is Ankara’s expanding military partnership with Kosovo – highlighted by the delivery of Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones and other defence cooperation initiatives in 2024/25 – that has triggered a sharp backlash from Serbia’s President, Aleksandar Vučić, who publicly condemned Ankara’s move, labelling it a “provocation that endangers stability in the region”, warning that Serbia “will not stand by while others arm those who threaten our people”. Likewise, Serbia’s Foreign Minister, Ivica Dačić accused Ankara of “undermining the EU-led dialogue process” between Belgrade and Pristina and of “taking sides” instead of promoting regional balance. Ankara, for its part, defended the sales as part of legitimate bilateral defence ties with a sovereign government and consistent with its NATO commitments. Yet the episode has strained the previously cautious Türkiye–Serbia relationship, exposing Ankara’s changing priorities in the Balkans – from its once even-handed diplomacy to a more assertive projection of influence through defence exports.

For regional observers, Türkiye cannot be dismissed as a peripheral actor. It is clearly a regional power with both hard capability and soft power influence. Its involvement suggests greater opportunity for procurement, capacity-building, training, joint exercises and regional architecture. Countries wishing to engage the Western Balkans therefore need to factor in Ankara’s role, its alignment and the dual track of Western/NATO membership.

Contributions to European security

On 30 October 2025, a Joint Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism was signed between the EU and Western Balkan partners. The plan plays a key role in the gradual integration of candidate countries into the EU’s security architecture, as well as in the context of the overall enlargement process. It also represents a renewed operational commitment for deeper regional security and defence cooperation, intended to equip the EU and the Western Balkans to face new and evolving threats, including online radicalisation, misuse of emerging technologies – drones for example – and the use of cryptocurrencies for financing terrorism.

More recently, the annual and eagerly awaited autumn European Commission country reports provide useful snapshots on prospective candidates for EU membership. When it comes to the region’s ‘frontrunner’ for EU membership – Montenegro – and the EU’s common security and defence policy (CSDP), the country continues to participate in EU crisis management missions and operations under the CSDP banner, including currently in the EU NAVFOR ATALANTA (headquartered at Rota Naval Base, Spain).

Fellow NATO member, North Macedonia, was praised for its continued and full alignment with the common foreign and security policy (CFSP), something that very much reflects its strategic choice. The EC Report recalled the bi-lateral Security and Defence Partnership signed in 2024, citing it as an excellent example of how North Macedonia and the EU are already coming closer “concretely increasing collaboration in key areas such as support to Ukraine, countering hybrid threats, and counter-terrorism.”

For Albania (another Balkan NATO member), the annual report noted that under the European Peace Facility (EPF), the EU had adopted assistance measures for Albania’s armed forces (roughly EUR 28 million in 2025) to enhance its deployment capacity and contribution to EU CSDP missions.

Potential flashpoints

As 2025 nears its end, a number of issues remain potential flashpoints for instability.

Kosovo–Serbia

For Serbia, the unresolved status of Kosovo (declared independence in 2008, unrecognised by Serbia) remains a core fault line. In line with its non-recognition policy, Belgrade vehemently objects to Kosovo’s inclusion in any defence cooperation arrangement such as the Albania–Croatia–Kosovo trilateral deal, viewing this as deeply destabilising. Türkiye’s support for Kosovo’s defence capacity is an additional source of Serbian grievance with Belgrade stating that Turkish drone deliveries to Kosovo is “neither easy nor good news”. The potential for sporadic violence and tension (for instance, in North Kosovo among four Serb-majority enclaves) remains high.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The internal political structure of BiH – divided between the two entities – the (Bosniak/Croat) Federation and the Serb-run Republika Srpska – remains fragile. Key risk elements include: Republika Srpska leadership cementing their secessionist rhetoric; external actors (Türkiye, Serbia, and Russia) maintaining influence on different sides of the domestic divide, possibly exacerbating local tensions; a local crisis (such as renewed violence, or constitutional breakdown) might attract external intervention or NATO/EU involvement, with broader implications.

External influence

The presence of multiple external actors (Türkiye, Russia, China, EU/NATO states, Gulf states) creates a multi-vector environment. There is the risk that states will deepen ties with one power to the exclusion of another, thereby reducing regional coherence and increasing external leverage over national defence policy. While the new trilateral pact (Albania–Croatia–Kosovo) and Türkiye’s greater engagement may serve to diminish Moscow’s exclusive influence, Russia still provides alternative pathways, which Balkan states may exploit in their multi-vector strategies. In this regard, defence industry providers are all competing for influence via sales, training, and local production. This all creates a richer supply-friendly environment.

Interestingly, at the end of 2025, Serbia’s relationship with Russia has soured as US sanctions on the Petroleum Industry of Serbia (NIS) – majority-owned by Russia’s Gazprom – have forced Belgrade to face the fragility of its energy dependence. Moscow’s reluctance to shield NIS has triggered sharp rhetoric between Serbian President Vučić and the Kremlin, revealing deeper disagreements over gas supplies and arms trade.

Defence industry opportunities

For the defence industries in the region, the Western Balkans offers a more diverse range of opportunities than a decade ago:

- Procurement variety: States are finally transitioning from legacy Soviet systems. Western systems (jet fighters, various armoured fighting vehicles, artillery), and mixed portfolios, are triggering greater demand.

- Local production and maintenance: States are looking to build maintenance, training, co-production capacity domestically.

- Hybrid domains: Cyber defence, drones, ISR, and logistics have assumed greater importance – smaller states will opt for greater agility over heavy armour.

- Regional pacts: Trilateral and other defence partnerships create joint procurement platforms, cost-sharing models, and interoperability frameworks; these are also attractive to suppliers.

Looking ahead to 2026

At the end of 2025, several developments will be critical to watch in the year ahead:

- How the operationalisation of the Albania–Croatia–Kosovo defence agreement manifests itself – whether it becomes meaningful or remains symbolic.

- Serbia’s path: whether it deepens the axis with Hungary, keeping in mind elections in spring 2026. Also, the state of Belgrade’s relations with Russia; could Belgrade perhaps take more steps into the Western orbit.

- BiH: whether further destabilising moves are taken in the Serb-run entity, Republika Srpska.

- Procurement flows: which platforms states opt for: Western/NATO vs Russian/Chinese.

- Hybrid-threat resilience: whether states build national capacity or remain vulnerable to influence operations, energy sabotage and disinformation.

- External power competition: how Russia, Türkiye, China, Gulf-states (via investment) and the West compete for influence and defence industry access.

Closing thoughts: A region at a crossroads

The Western Balkans region should no longer be treated as a peripheral concern in the context of wider European security. Against the backdrop of the dramatically altered European security setting since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has become an area of strategic readjustment and external competition. From Zagreb to Tirana to Pristina; to Belgrade and Sarajevo – the defence and security dimension of this corner of Europe is back on the map. Aspiring EU members actively participate in various EU missions, but as highlighted above, opportunity often comes with risk as the role of external actors will continue to pose a threat – to the security and stability of BiH for example. Elsewhere, much will depend on whether Serbia decides to commit more seriously to a European future and loosen ties with Moscow, as other states advance towards full EU membership. And for the all-important defence-industry players, engaging the Western Balkans is timely and much-needed. But for them especially, understanding the alignment choices for states of the region is crucial. For policy analysts, the region provides an early indicator of how a contested European security environment could take shape and evolve. Finally, for NATO and the EU, the time to step up and engage in a more coherent and strategic manner in the region is now.

Lincoln Gardner