Chemical weapons remain a persistent threat, but advances in protective clothing are changing the calculus of CBRN warfare. This piece explores how new fabric technologies are making suits lighter, safer, and more effective.

Chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) hazards drive the development of defensive countermeasures such as protective masks or medical treatment. In the area of protective clothing, the aspect of the CBRN threat that drives the entire segment is the chemical weapons threat. Generally speaking, gamma rays pass right through CBRN suits anyway, and radioactive particles and biological aerosols are far easier to mitigate than nerve agents and blister agents. So, what we are really talking about with ‘CBRN suits’ is chemical warfare protective clothing.

One of the reasons chemical warfare is not more widespread on the battlefield is that it is a category of warfare whose effects can be minimised with training and equipment. The offensive chemical weapons arms race that occurred in the First World War was quickly accompanied by a parallel arms race in defensive technology. The bulk of chemical warfare fatalities in that war occurred in the armies that were slow in fielding effective gas masks, namely Russia and Italy. This set a pattern that was repeated in later conflicts such as the China-Japan front in the Second World War, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and the Iran-Iraq war. The side in the conflict that fielded more and better protective clothing and respiratory protection tended to have far fewer chemical casualties.

During most of the Cold War, both Soviet and Western chemical warfare and chemical defence doctrine acknowledged that chemical weapons had decreased in their ability to cause immediate casualties among trained and well-equipped troops, due to protective clothing, respiratory protection, detection, and decontamination. Much emphasis was rightly placed on the fact that use of chemical warfare agents, particularly persistent liquid agents like Mustard and VX, would drive intensive use of chemical protective clothing and thus degrade the enemy’s operations due to the cumbersome nature of the clothing.

While the First World War is now beyond memory and the chemical defensive doctrine of the Cold War is now, increasingly, the province of aged commentators like this correspondent, the fundamental reality remains true. Chemical protective clothing and respiratory protection erodes the lethality of chemical warfare. But the corollary is also true; the prospect of spending days or weeks in chemical protective posture erodes every aspect of military operations and increases casualties from accidents and heat injury. For this reason, it is worth looking at the history of chemical protective clothing and how we got to where we are today.

Wax capes and rubber suits

Chemical protective clothing as a component of protective equipment, as opposed to merely gas masks, arises from the end of the First World War. In effect, the first few generations of chemical warfare agents in that gruesome war were things like chlorine and phosgene, which are almost entirely respiratory threats defeated by a good respirator. This started to change with the advent of blister agents, such as sulphur mustard, also known as ‘yperite’ or misleadingly as ‘mustard gas’ in the last year of the war. Mustard, and other chemicals like lewisite, were active through the skin as much or even more than through the lungs.

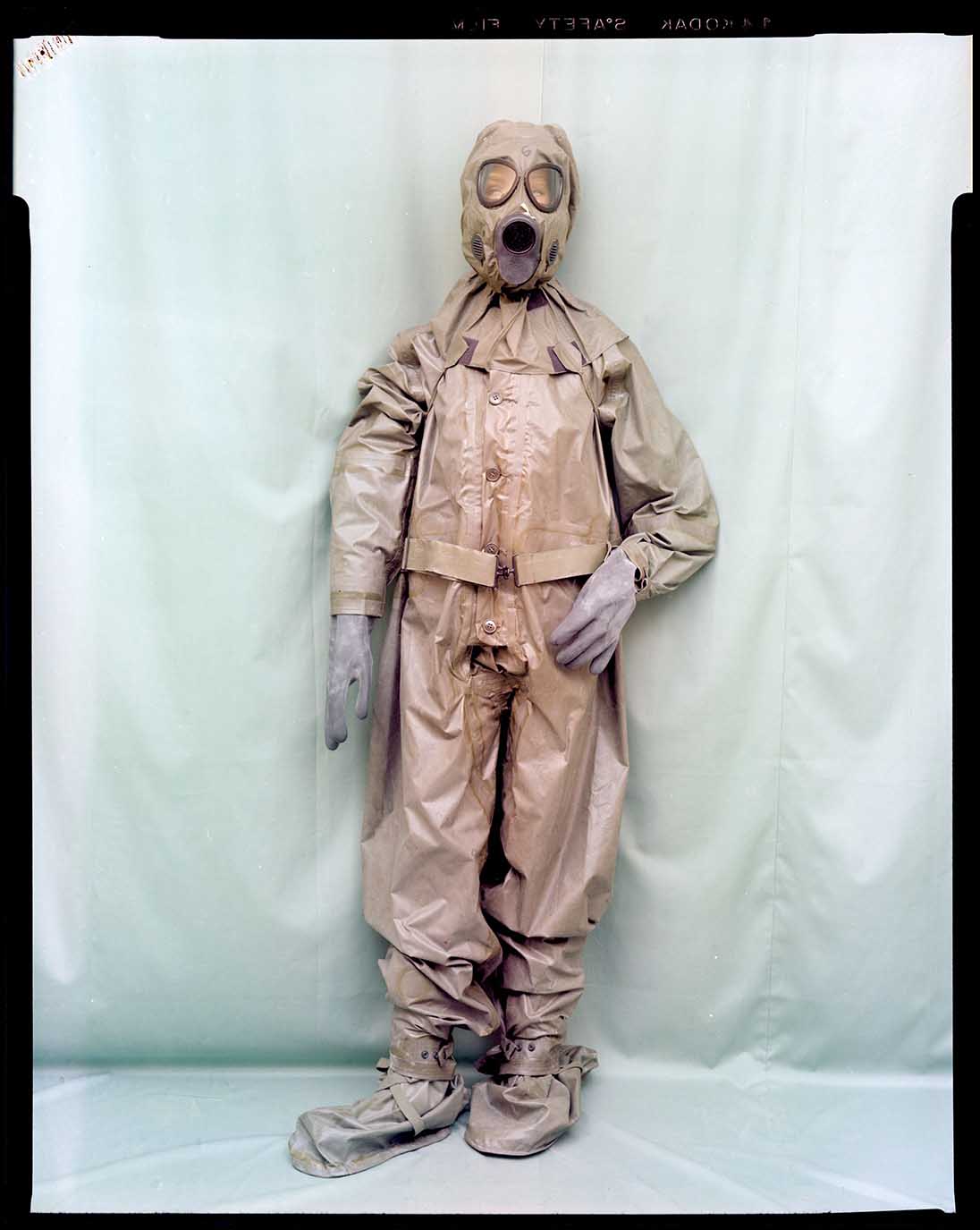

For basically 50 years after the advent of the blister agents and their even more dangerous counterparts, nerve agents, which were also active through skin content, protective clothing to protect against them was fairly unsophisticated. Generally speaking, protective clothing was rubber or rubberised cloth for specialist chemical troops, with wax-impregnated uniforms and capes for normal soldiers. For example, the US Army fielded both wax-impregnated uniforms for front line soldiers during key offensive operations such as the D-Day invasion and also had numerous Chemical Warfare Service units whose job would be to treat literally millions of uniforms with wax should chemical warfare break out. These wax-impregnated uniforms and capes were, by no means, completely effective but were meant to mitigate possible mass casualty events stemming from the use of blister agents.

Eventually, by the 1960s and 1970s, as the Cold War became entrenched, chemical protective clothing could be broadly categorised into non-permeable and permeable suits. Non-permeable suits do what they say on the label. They form a barrier between inside and outside. First made of rubber or rubberised material, they have long proven problematic due to heat stress to the wearer. If troops wore them for any extended period of time, there would be a serious amount of heat casualties in all but the coldest weather, and the chemical warfare agents that need the most skin protection are far less effective in colder weather anyway. The Soviet-era OZK suit is still very much in use in Russia and some other ex-Soviet states. In the West, non-permeable suits are more the province of civil-sector emergency responders, where more advanced materials made by companies like DuPont and Trelleborg are used to make partially-encapsulating and totally-encapsulating suits for hazardous materials incidents, which often deal with substances far more physically corrosive than chemical warfare agents. In addition, such incident response rarely requires a technician to wear a suit for more than about an hour at a stretch, as opposed to days or weeks.

Permeable suits arose in NATO militaries as a way to have chemical warfare protection that lasted a long time in the field and allowed the wearer to operate for a long time without falling over from heat injuries. A permeable suit would have to let some moisture out and let some of the external hazards in, but if made correctly a suit could have one of more layers of material that would absorb or adsorb the chemical warfare agent. In effect, such a suit would be a bit like a protective mask filter.

Earlier generations of permeable suits included the US Chemical Protective Overgarment CPOG (late 1960s onward) and Battle Dress Overgarment BDO (late 1980s), as well as the UK Mk II and Mk III suits. Other NATO countries had similar designs, although some also used US suits. Individual designs varied, but the CPOG and BDO were (and still are, in some places) typical examples. They had a fabric outer layer, usually with some waterproofing, and a polyurethane or similar foam inner layer that contained charcoal powder. These suits were infamous for leaching powder onto the wearer. The BDO was nominally good for three weeks of continuous wear before disposal.

The 1990s saw a generation shift to lighter, more effective suits. Several technical approaches were used. Small carbon spheres in the fabric, impregnated carbon fabric, and activated carbon fabric all used more sophisticated forms of carbon adsorption than the bulk charcoal of the older suits. By using carbon more efficiently, these suits are lighter and thinner than the charcoal suits. A carbon sphere fabric was adopted by the US Department of Defense to make the Joint Service Lightweight Integrated Suit Technology protective ensemble. The US government spent hundreds of millions of dollars on procuring these new suits, with 96 million USD spent in Fiscal Year 2003 alone.

The new carbon sphere suits, both the US JSLIST suits and numerous other very similar products around the world reaped significant benefits over older technology. A higher level of protection was afforded by a thinner and lighter suit that gave significantly less heat burden. In addition, the suits could be laundered several times and had a functional lifetime at least twice, if not longer, than older charcoal suits. While CBRN suits have never been popular with troops, these newer ones were widely regarded as superior. Although they are more expensive than older charcoal suits, the incremental expense was partially offset by the improvements to service lifetime, bulk, and weight.

The new frontier

One obvious problem with porous, breathable suits is that they retain the chemical hazards within them. Even if the chemical warfare agents are absorbed or adsorbed into charcoal or carbon spheres, the used suit becomes hazardous waste. What do you do with it? What if the actual fabric of the suit could react with chemical warfare agents and, instead of merely containing the threat, actually cause some reaction that would neutralise the threat? A decade ago, this would have sounded either like fiction or unrealistically expensive to this correspondent.

This is where Heathcoat Fabrics, a centuries-old textile company in Tiverton, UK comes into the equation. This correspondent visited the factory in October 2025 to look into their relatively new chemical defensive clothing technology. Heathcoat has migrated from a traditional English textile weaver into a modern high-tech textile operation employing five hundred or so employees. Their work has spawned a new generation of protective clothing technology.

The new frontier is a chemical compound called zirconium hydroxide, a chemical with non-CBRN industry applications up until recent years. A number of published studies and several patents show that zirconium hydroxide in powder form can degrade the major liquid chemical warfare agents, such as nerve agents and sulphur mustard. The zirconium hydroxide readily adsorbs these agents and reacts with them to neutralise them.

Heathcoat takes the theoretical properties of the zirconium hydroxide and applies them to clothing. Using a proprietary process that has its roots in making the previous generation carbon sphere fabrics, Heathcoat can bond zirconium hydroxide to a layer of fabric. This zirconium hydroxide fabric can then be stitched into a suit, or used on its own as a decontamination mitt, which may well feature in future articles on the subject of decontamination. Heathcoat refers to this as its ‘NeutraliZr’ product line (a portmanteau of ‘neutraliser’ and the chemical symbol for zirconium).

A chemical protective suit with zirconium hydroxide provides significant advantages over previous generations of CBRN fabrics. The various activated carbon fabric of the previous generation suits used toxic and environmentally concerning PFAS (so-called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in their manufacturing process. These ‘forever chemicals’ are of necessary concern to environmentalists, the public, and regulators; as such, manufacturers would do well to find ways to avoid them. The zirconium hydroxide fabric avoids PFAS and leads to a less environmentally troublesome manufacturing process. Depending on how much of the zirconium hydroxide is incorporated in the fabric, suits that provide a higher degree of protection than even the best activated carbon fabric suit are theoretically feasible. Shelf life is excellent, as is launderability of the suits. Because the suits themselves act to decontaminate adsorbed chemical warfare agents, used suits are less of an environmental hazard than previous generations. None of the world’s major militaries has seriously addressed what to do with the potential waste stream of thousands of contaminated suits, leading to off-piste discussions about dumps and burn pits reminiscent of the negligence noted in a previous article (See: ‘Toxic legacies of warfare: Burn pits and other health hazards’ in ESD 07/08-25).

One downside is that these suits are somewhat more expensive than previous generations. Understandably, Heathcoat would not tell this correspondent how much they pay for their zirconium, but open-source research online does show a significant price differential over activated carbon. Some of the price differential with the newer generation of suits would be compensated for by gains in shelf life and longer service lifetimes. Heathcoat Fabrics, it should be noted, does not make chemical protective suits but supplies such manufacturers. Observers of the CBRN industry would do well to watch both Heathcoat and its customers, as this correspondent has not seen such a step change in the CBRN industry in well over a decade.

It is worth noting that there is a rival technology to zirconium hydroxide. So-called ‘Metal Organic Frameworks’ (MOFs) have appeared frequently in the technical literature with claims and properties not dissimilar to zirconium hydroxide. MOFs have been clearly demonstrated to react with the nerve and blister agents that are the main threat driving the CBRN protective clothing market. These properties have been known for some years now. Of considerable interest is an article in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in December 2019 by a team principally affiliated with Northwestern University (Chicago, USA) and the US Army. (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 51, 20016–20021 for those interested.) This article specifically talks about incorporating MOFs into textile fibres for detoxifying nerve agents.

MOFs could, all other factors being equal, give Heathcoat and the zirconium hydroxide some competition. But it seems all other factors are not equal. MOFs, or at least the ones discussed seriously so far, all seem to be considerably more expensive than zirconium hydroxide. There may well be a place for MOFs in chemical warfare protection or decontamination, but barring a radical improvement in their costs, it seems unlikely at this point that a rival suit could be commercially competitive.

It would be remiss to not point out the dark side of the equation. All of these suits are still permeable. Something small enough could theoretically work their way through any of these types of suits. As noted in a previous article (See: ‘Nanotechnology: Threats and prospects in the CBRN sector’ in ESD 09-2025), nanoparticles could encapsulate some chemical or biological threats. A small enough nanoparticle could insinuate itself through all of these permeable suits. In which case, we are back to impermeable suits. At this point, this is merely hypothetical.

The future

As mentioned above, the type of step-change represented by zirconium hydroxide does not come along very often in CBRN defence technology and its significance should be noted. The logical end-state in CBRN protective clothing is a regular combat duty uniform which is, by means of its fabrics, also a chemical protective suit. We are not quite there yet, but things like zirconium hydroxide and MOFs are a step in that direction.

The rate at which newer suit technologies displace the older ones has always varied. We can expect older technologies to remain in use for a long time as some countries under-invest in CBRN defence, often for reasonable prioritisation of scarce defence resources. However, after a quarter century of, dare one say it, boring gradual change, the chemical protective fabric segment of the industry has now become much more interesting.

Dan Kaszeta